A Wooly History In My Own Back Yard

Strolling out of the Boston Commons, I couldn't help but imagine myself as an early Boston wool baron.

September 28, 2023

By Oliver Charles

US Merino Wool Sweaters

Introducing the 3rd blog in my 4-part blog series about US Merino Wool Sweaters. This blog is all about the history of US merino wool.

- Ultimate Guide to Merino Wool

- US Merino Certifications

- History Of US Merino Wool

- 10 Common Merino Misconceptions

----------

Typically, when we launch a product line that uses a brand-new material, I like to take the new sweaters on a bit of an adventure. It's my way of welcoming them into the world.

Leading up to the launch of our 100% US-Made Merino Sweaters, I knew exactly what I wanted to do. I wanted to take the sweaters to a sheep farm. Living in New England, it seemed like a no-brainer because there is an abundance of farms within a stone's throw of Boston.

However, my plans were quickly thwarted when I learned the farms were extremely wary of strangers. I called 7 small-scale sheep farms, and none wanted anything to do with me and my desire to befriend their sheep.

Needless to say, I was quite perplexed. My perplexion led me to dig into the history of the wool trade in Boston, which is surprisingly rich.

So I figured I'd put on my sweater and head to the local pub and write about the history of the wool trade.

Slater, wearing his US Merino Crew Neck, writes about the history of wool in the US.

Merino Mania

I will venture to guess you've likely heard of merino wool before. In fact, I'd bet you either own some or have owned some in the past; Nothing as lovely as our 100% US-Made Merino Sweaters, of course. Nevertheless, I bet you're familiar with merino wool.

Today, merino is synonymous with New Zealand and Australia. Soon to be America, too, we hope.

However, the breed originated in Spain, where its ultra-fine, highly prized wool was a closely guarded commodity. By the 14th century, the export of merino wool was a staple of the Spanish economy.

In fact, according to the book The Sheep and Man," at the height of the merino's importance, it was a capital offense to export the sheep."

With the exception of gifts to royalty and the occasional smuggling operation, there were no real exports of the Merino Breed from Spain until the early 1800s.

Smuggling Sheep

A man by the name of William Foster was the first documented person to have smuggled the prized breed from Spain to Boston in 1793. Unfortunately, Mr. Foster made the mistake of leaving the sheep in the care of a friend while he traveled for business.

Said friend, not knowing their value, quickly made a meal out of the three sheep. A few years later, that same friend would end up paying $1,000 per sheep, equivalent to 31,000 in today's dollars.

Over the next few years, many famous revolutionists, including The du Pont family, would smuggle a sheep or two from Spain to the United States.

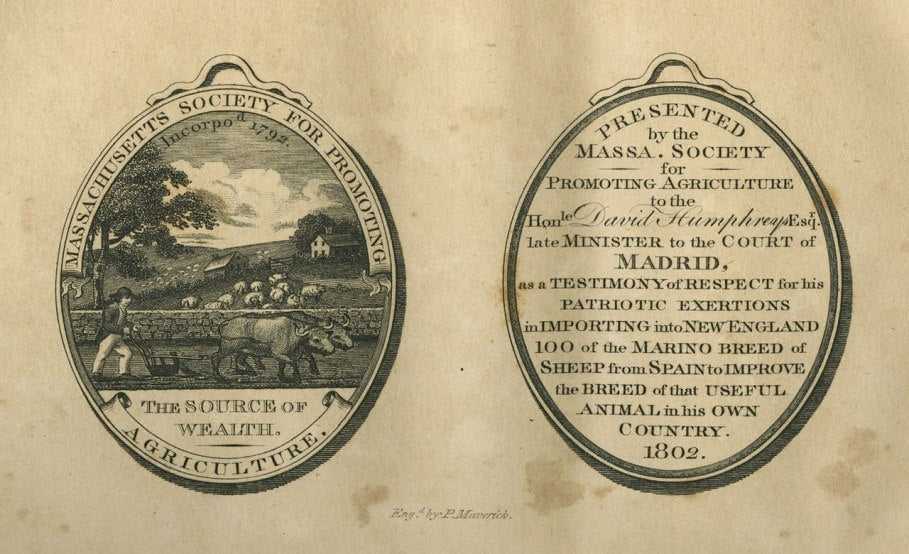

It wasn't until the turn of the century when Colonel Humphreys, minister to Spain and close personal friend of George Washington, brought 100 Sheep to his home in Connecticut that the breed began to get a foothold in the new world.

The Rise Of Merino Boom And Bust

Even as more and more merino began to populate America's northeast, there wasn't much of a market for the fine wool produced by the breed.

At that time, the American textile industry had not yet experienced significant expansion, wool prices remained low, and dedicating resources solely to sheep farming for wool was not a particularly lucrative endeavor.

The fabrics produced by the limited number of commercial mills paled in comparison to the quality and variety of textiles obtainable through trade.

Colonel Humphrey's Wool Mill.

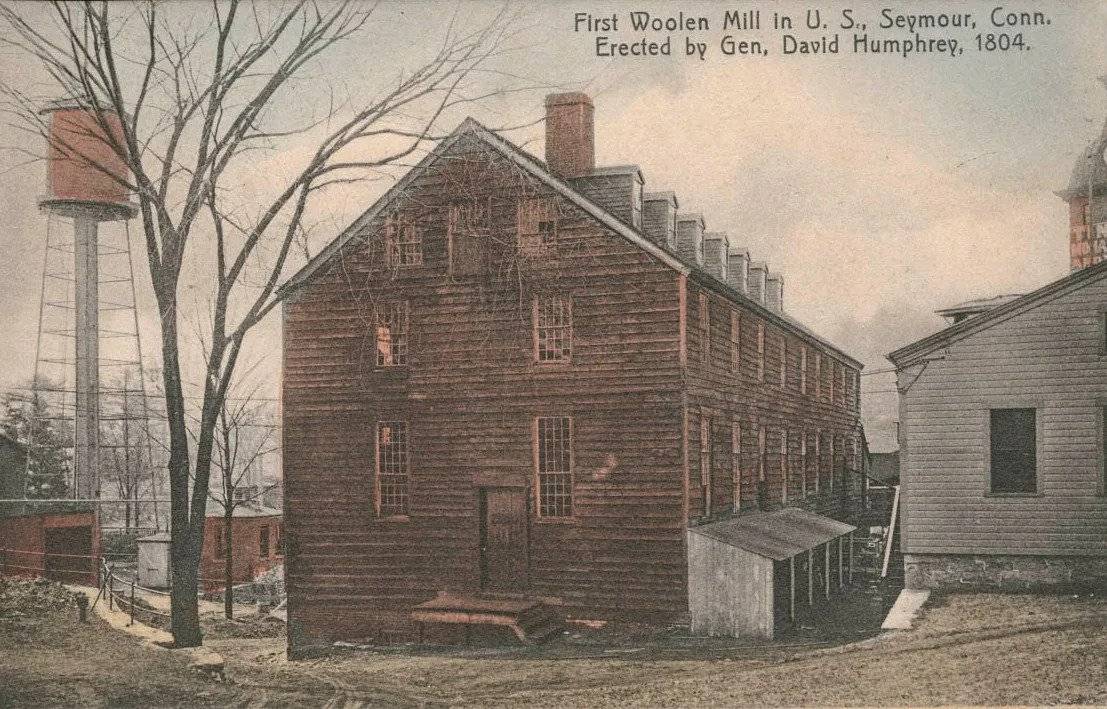

However, things began to change as affluent farmers like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson recognized the promising potential of sheep.

In the beginning, Jefferson's primary focus was on the affordability and utility of sheep.

His initial objective for keeping sheep was not centered around wool production but rather aimed at revitalizing his land, which had suffered depletion due to continuous corn and tobacco cultivation.

Soon, everything would change when the Embargo Act of December 1807 severely restricted trade with England. Causing a significant disruption in the supply of fine wool that had previously been predominantly sourced from Spanish and French flocks. This shift necessitated the exploration of alternative trade routes, leading to a surge in profitability and popularity in obtaining and raising merinos.

Jefferson wrote to the Marquis de Lafayette, referring to the embargo, "It has produced one very happy and permanent effect. It has set us on domestic manufacturing and will, I verily believe, reduce our future demands on England fully in half. We are all eager to get into the merino race of sheep."

Merino sheep on the White House lawn while Jefferson was president.

Many early revolutionists saw this as an opportunity to build the American economy. States even provided incentives and rewards to motivate farmers, focusing on encouraging merino raising.

The demand for wool was further bolstered when the War of 1812 broke out, and the army needed wool for uniforms.

In Vermont, thousands of acres of trees were cut down to provide grazing land for the new flocks. By the year 1835, there were over 1,000,000 merino sheep in the state alone. By 1840, New England had nearly 4,000,000 merino sheep.

However, as the war ended and trade embargos and protective tariffs were lifted, the price of wool began to plummet. Even more so for the fine fiber of merino. Neither the western expanse nor the agricultural south required fine clothing.

Sheep that had once commanded a price of $1,500 just four years prior now sold for $50.

While the Merino Craze may have ended by the late mid to late 1800s, the sheep and the industry were here to stay. The US and, more specifically, Boston still had an important role to play.

The Street Before Wall Street

Starting around the 1880s, the vast majority of sheep herding had moved west to states like Oregon, Washington, and California. Towns in Oregon like Shaniko, our wool’s namesake, enjoyed brief moments as boom towns.

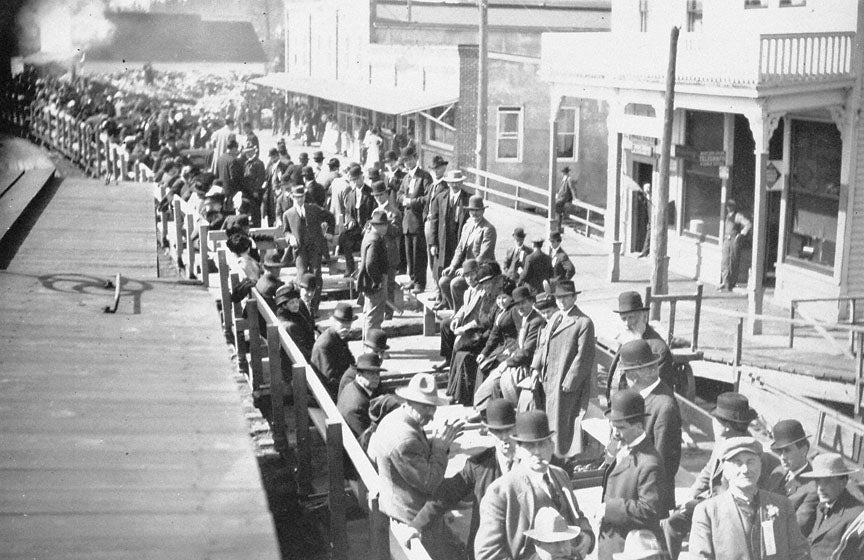

Wool Buyers In Shaniko at the turn of the 20th century.

However, industrial infrastructure for processing wool was still situated in the northeast or, more specifically, in Boston.

One street, in particular, played an important role due to its proximity to good water and rail ports, making shipping wool to Boston very inexpensive for the wool growers.

The Street's official name was Summer Street, but it was affectionally referred to as The Street by most in those times.

Grading the wool was a crucial task that The Street could efficiently execute, thanks to its proximity to a substantial pool of skilled wool experts who had settled nearby in South Boston.

Moreover, The Street boasted ample office space and well-equipped warehouses capable of managing and storing substantial quantities of wool.

The Plaque Commemorating the Wool Trade in Boston.

I Had To See It For Myself!

Upon learning about The Street and its rich history, I had no choice but to go and see it for myself. So I gathered my things, left the cozy pub I was writing this very story in, and ventured out in the rain to Summer Street.

The first stop was Boston Common because I can't really visit any historical sites in Boston without first paying homage to the famous park.

Slater, in his US Merino Crew Neck, walking Boston Commons to see The Street.

It was quintessential New England weather, and as I strolled out of The Commons down through the city, I couldn't help but imagine myself as an early Boston wool baron. After making my way through the hustle and bustle of the city, I emerged to a view of what used to be the city's industrial heart, once called The Street.

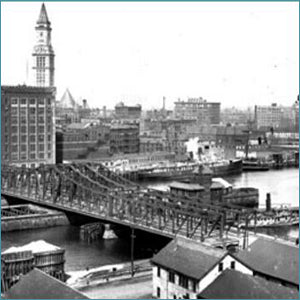

The Bridge across the Fort Point Canal then and now.

Before heading across the bridge, I spent a minute thinking about what it must have been like back in the early 1900s. I like to think the streets were filled with young folks resembling Jack and myself. Each one headed to a different wool supplier to pitch them on their new sweater company.

After emerging from my daydream due to a particularly fierce gust of wet wind, I crossed the bridge and found the plaque commemorating The Street as the Wool Capital of the United States.

Slater, in his US Merino Crew Neck, in front of the plaque commemorating the Boston Wool Trade.

The Street is a historical site in Boston, so the old buildings here have been preserved. Well, the outside of them has. The insides are now swanky apartments and office buildings. But these used to be the very warehouses that processed millions upon millions of pounds of merino and other wool.

The Street Wool Warehouses then and now.

The spirit of The Street lives on, though, as the area is now home to Boston's newest innovation district and houses many of the city's high-tech companies and their workers.

The Sheep Industry Today

In 2022, the US only produced 22.2 million pounds of wool, a shell of what it once was. However, many active herders, mills, and businesses still have kept the tradition alive.

We are grateful to businesses like Shaniko for keeping the industry alive and giving it the investment it deserves to thrive. Hopefully, we can help get that 22.2 Million number up to at least 22.21 million by the end of next year.

Or even better, you'll love our new US Merino Crew Neck so much that we'll trigger a new Merino Craze, and The Street will make a heroic comeback with Oliver Charles at the center of it all.

If you believe that every good wardrobe starts with owning less and owning better, consider buying yourself an OLIVER CHARLES sweater.

Shop NowWhat Is The Warmest Wool? My Yak Wool Story

How to find the warmest sweater possible while building a durable, low maintenance capsule wardrobe.

Read moreThe Astronomical Perks Of A SeaCell Sweater

Styling a satisfying, sensible, and stellar piece of clothing.

Read moreBenefits Of Being An Outfit Repeater

Outfit repeating made easy with a game-changing capsule piece.

Read morePacking A Capsule Wardrobe For Travel

Testing the packability of the Oliver Charles All-Season Quarter Zip.

Read more